Clonony Castle has changed hands many times through the centuries, and indeed even within the last ten years it was sold on the open market. For less than seven hundred thousand euros, you could have owned a castle with more than its fair share of mysteries. Previous residents included a German-born Italian noble, descended from Albanian royalty, a man most famous as the husband of “Lady Loony”, and two sisters who, history would assure us, never actually existed. But we’ll get to these residents in due time. For the moment, then, let us start with the Mac Coghlans.

Clonony was built by the Mac Coghlans some time in the early 16th century. The exact date is not known, but the style fits with the Tudor period. It definitely was built by 1519, for then, according to the Four Masters, during a conflict between rival Mac Coghlans “James Mac Coghlan, prior of Gallen, and heir presumptive of Delvin Eathra, was killed by the shot of a ball from the Castle of Cluan Damhna.” This is one of the first recorded death by gunfire in Irish history. The Mac Coghlans were one of the royal clans of Leinster, eligible to take the Kingship of the province, and this led to more than the usual internal strife in the clan. At some point, the Mac Coghlans ceded the castle to Henry VIII, and in fact a portion of the clan would renounce their Catholic faith to become Anglicans under Henry and Elizabeth. They appear to have retained the surrounding township, however, or perhaps remained as stewards of the castle as during a war between the Mac Coghlan clan and “the descendants of Farrell and O’Molloy” in 1553, a notable incident took place at Clonony. According to the Four Masters:

“[A] peasant of the people of the town acted treacherously towards the warders of the town, and slew three distinguished men of them with a chopping-axe, tied a woman who was within, and then took possession of the castle; and this was a bold achievement for one churl!”

Archaeologists have found skeletons, swords and Elizabethan coins around the castle, which may relate to whatever fighting took place in this period. Sadly, we don’t know any more about this remarkable episode. We don’t even know who owned the castle at this time – though we do know who had owned it after it was ceded by the Mac Coghlan. It was a gift from the king, to the man he would have as his father in law.

Thomas Boleyn’s position in the Tudor court was hardly novel. The influence of a new Queen’s family on the throne had always been a source of tension in the court, as had been demonstrated by the Wars of the Roses a few centuries earlier. Still, his daughter Anne’s advance on the throne required that her family be ennobled, and so it was that Thomas was granted several titles and possessions from the king – among them Clonony Castle. Sadly, as is well-recorded, Anne was unable to give the king the heir he sought and so it was that she ended her days on the headsman’s block, with her father forced to assent to her execution. Also executed was her brother George, who was accused of incest with her. George left behind a widow (who would also be executed ten years later, for assisting in the adultery of Henry VIII’s fifth wife Catherine Howard). According to the official history he never had any children. However, a grave in Clonony would disagree.

A pair of pictures at nearby Birr Castle, that some speculate may depict the Clonony Boleyn sisters.

In 1868, the Historical and Archaeological Society of Ireland were presented with a rubbing from a tomb slab found near Clonony. The slab had reportedly been in a cave twelve feet underground, about a hundred yards from the castle, had been found by workmen gathering stone for work on the castle. They found a stone coffin, with the remains of two bodies. The two bodies were moved to a local graveyard, while the slab was put on display in the castle grounds, where it still is today. The slab became known as the monument of “Queen Elizabeth’s cousins”, and reads:

“Here under leys Elisabeth and Mary Bullyn, daughters of Thomas Bullyn, son of George Bullyn the son of George Bullyn Viscount Rochford son of Sir Thomas Bullyn Erle of Ormond and Willsheere.”

It is possible that the George it refers to was an illegitimate son of the Viscount Rochford, and if so he may have moved to Ireland to get away from the fallout of his father’s death. Local legend definitely holds this belief, and claims that the two girls were this son’s grand-daughters. When Elizabeth died young, Mary was so grief stricken that she threw herself from the tower of the castle to her death. As a suicide, she could not be buried in the graveyard, but the father could not bear to part the two and so they were both interred in unconsecrated ground. The priest in 1803 had a softer heart, however, and besides he could not know the truth of the matter, so he erred on the side of compassion and allowed them in the graveyard.

One of the many statues, both inside and outside Albania, that honour Sir Matthew de Renzi’s illustrious ancestor Skanderbeg.

Although the slab is not dated, if the tale of the two sisters is true it may explain why the castle was sold to a foreigner some time in the early 17th century. Sir Matthew De Renzi was, according to his tomb in Athlone, born in Cologne in Germany. He claimed descent from George Kastrioti, an Albanian hero better known by the tile of Skanderbeg. Skanderbeg was a corruption of the Turkish title Iskender Bey, “Leader Alexander”, which he was given when he served the Ottoman Empire as a general. In 1443 he left the empire’s service and established the first unified Albanian state, which he would defend against those same Turks for the rest of his life. He formed a lifelong alliance with the Kingdom of Naples, and after his death is widow and son moved there, and it is from them that De Renzi claims descent. Quite how his family wound up in Cologne, or indeed how he wound up in Ireland, we may never know. He gained grants of land in Ireland in 1622, was knighted in 1627, and is credited on his tombstone with the creation of the first English-Gaelic dictionary. His tomb was erected by his son, also named Matthew, and letters from both are recorded in the National Library of Ireland. The younger Matthew was an attorney and served as an agent for collecting rent, and went on to side with Cromwell during the Irish Confederate wars, exchanging correspondence with James Cranfield, the Earl of Middlesex. Quite how he fared in the Restoration is unknown, but a clue may be found in the works of the Irish poet Thomas Furlong. His final poem, published posthumously, was “The Doom of Derenzie”. It is apparently based on real characters, if not events, and tells the tale of Shane Wrue(doubtless a corruption of Sean Rua, which means Red John), an Irish wizard. He is left to bring up his niece after her parents pass away, and she becomes the apple of his eye. The niece is “seduced” by the young scion of the Derenzie landlord family, before he goes off to the wars, and this enrages Wrue. Though young Derenzie does marry the girl when he returns from the wars, Wrue’s curse hangs over him and eventually leads to his execution for a crime he may not have committed. The poem is rough around the edges, but showed definite promise and led many to declare that Furlong could have been one of Ireland’s great poets if not for his early death.

Regardless of the eventual doom that befell the De Renzies of Clonony, however, it is definite that when Furlong was writing his poem they did not own Clonony Castle any more. Instead it belonged to a barrister named Edmund Moloney, who is chiefly remembered by history for the singular tombstone he erected for his second wife Jane. The tombstone is in St Matthew’s Church in Bayswater in London. The epitaph thereon runs to over three hundred words, and tells not only of Jane’s first two marriages, but also goes into a lengthy digression on the family of Moloney’s first wife, who was confusingly also called Jane and whose family name was Malone. Edmund also comments on how Jane (the second Jane) was “hot, passionate and tender…a superb drawer in watercolours.” It concludes “For of such is the kingdom of heaven.” The tomb acquired some infamy, being referred to as the grave of “Lady O’Looney”, and it appears in garbled form in cheap books of “humorous” epitaphs to this day. Edmund also appears as a character in The Profligate Son, a book by Nicola Phillips which tells the sad tale of William Jackson, who was a son of Jane Moloney’s second marriage.

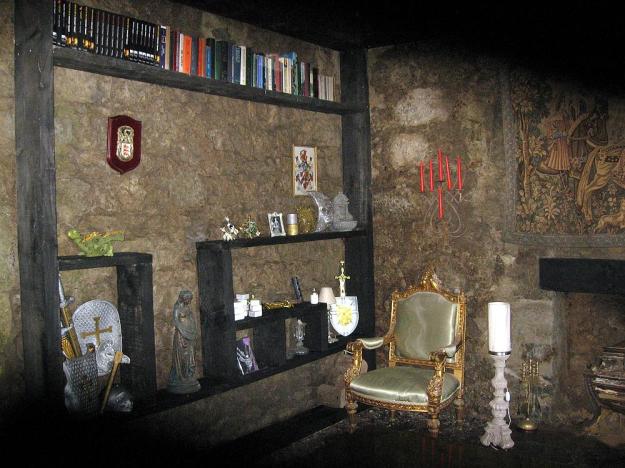

The castle was abandoned at some point after Edmund’s ownership, attracting local tales of a strange “thin man” seen standing atop the tower as people passed in the fading light. Currently it is in private hands, and is slowly being restored (though Irish laws on private restoration make that a laborious process). The owner allows visitors, though some courtesy is of course required, and a donation to the restoration fund is always welcome. It’s a worthy cause – the castle is one of the best examples of the Tudor style in Ireland, and between the Boleyns and the De Renzies, a prime example of the influence of outside forces on Irish life. At least, unlike so many castles, Clonony is unlikely to vanish into the hills.

Pingback: Today’s Scribbling: Clonony Castle – A tale of three tombstones | Daily Scribbling