William the Conqueror’s death in 1087 led immediately to the division of his kingdom between his two eldest surviving sons, Robert Curthose and William Rufus. While Robert was the eldest, he was far from the favourite. Indeed, ten years earlier Robert had rebelled against his father’s rule in response to his father refusing to take his side in an argument with his brothers – an omen of things to come. As a result, William on his deathbed considered disinheriting Robert, but was persuaded by his nobles to grant him the Dukedom of Normandy, and to give William Rufus the throne of England. The nobles were fond of Robert, perhaps because of his drunken nature and easily directed temper. The youngest son, Henry, received a gift of money with which to buy himself land. At first William Rufus and Robert remained on friendly terms, but that did not last long. Nobles with estates in both England and Normandy sought to reunite the kingdom under Robert, but when Robert failed to appear in England as they expected, Rufus soon crushed the rebellion, leaving himself secure on the English throne.

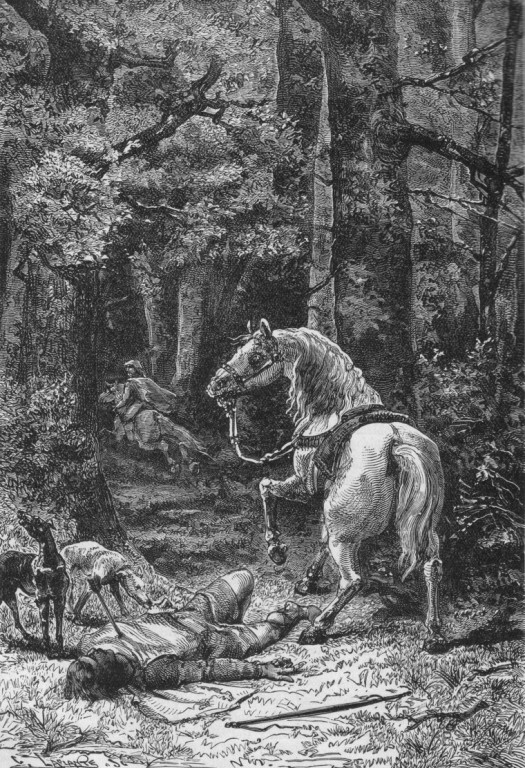

Rufus ruled with an iron fist and was not well-liked, a situation that was worsened when his brother Robert sought to go on the first Crusade, and mortgaged Normandy to him for 10,000 marks (about a quarter of the annual income of the throne at the time). Rufus raised the money through a brutally enforced tax on his subjects. Given this, Rufus’ death in a “hunting accident” is often regarded with some suspicion – suspicion given substance by the fact that his brother Henry, who was in the hunting party, left his body lying in the forest and rushed off to claim the throne.

Henry’s history through the thirteen years since his father’s death had been an interesting one. He inherited five thousand marks from his father’s estate, along with his mother’s estates in England. When the English nobles rebelled against Rufus, Henry was reluctant to take a part, as he was afraid that his money would be stolen by Robert if he left Normandy. In response, Rufus seized his estates in England. This left him landless, but he managed to buy a county from Robert for three thousand marks, to fund Robert’s invasion of England (which never actually happened). Once the rebellion had died down he travelled to England to appeal for the return of his mother’s estates, but Rufus refused. When he returned the bishop Odo (who regarded him as dangerous) persuaded the king to confiscate his county and imprison him, although he was soon released. Despite the lack of any title, however, Henry had established a solid powerbase in western Normandy, where he stayed for a while. When Rufus persuaded one of Robert’s vassals to rebel, however, Henry came to his brother’s aid, distinguishing himself in battle and personally slaying the rebel. Despite (or perhaps because of) these heroics, Robert tried to force him to leave Normandy, but was distracted by an invasion by Rufus. Rufus and Robert came to terms, but one of the things they agreed was to make each other their heir, cutting Henry out. However Henry consolidated his power and soon began taking over most of Normandy, with Rufus’ covert support, a process which accelerated when Robert went on crusade. He became a regular at Rufus’ court, and the two appeared close – until Rufus’ untimely death.

Drawing of Henry I’s coronation, found on a medieval manuscript.

While the manuscript dates to the 11th century, the drawing was added in the 17th.

Henry’s claim to the throne above Robert was based around the old tradition, taken from the Romans, of being “born to the purple”. He argued that as he had been born after 1066, and thus was the child of a reigning king, this gave him a greater claim than Robert who was merely the son of a Duke. This somewhat thin claim was given weight by both Henry’s presence and his reputation, and he managed to take over power relatively smoothly. He consolidated his power by marrying the daughter of the king of Scotland – who was also the niece of the late Edgar the AEtheling, last Saxon claimant to the throne. (The Scottish monarchy was closely affiliated with the Saxons – her brother, the future king David I, would marry Maud, the daughter of our old friend Waltheof.)

Matilda of Scotland, Henry’s first wife.

She may be the “fair lady” from the nursery rhyme London Bridge Is Falling Down

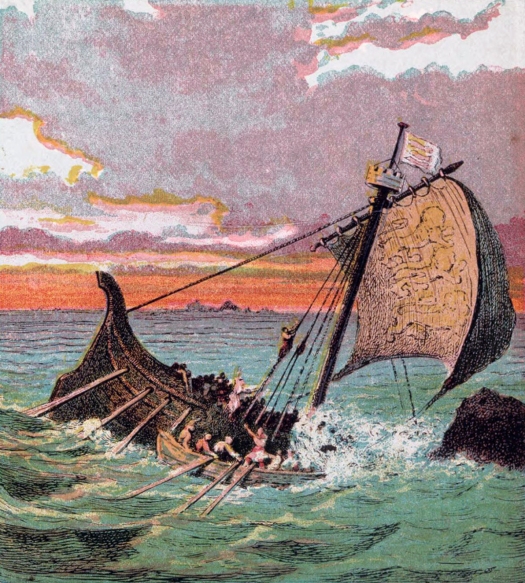

With the throne secured for Henry, his brother Robert (freshly returned from the Crusades) was not able to budge him – his one attempt at invasion ended disastrously and he was forced to renounce his claim. His continual attempts to stir trouble led Henry to invade Normandy five years later, and Robert was defeated and captured. Henry claimed Normandy as a crown possession, while Robert was imprisoned. He would remain a prisoner for the remaining twenty eight years of his life. With his brother defeated and the realm reunited, everything looked perfect for Henry – until 1120, when a single shipwreck changed the course of British history forever.

Henry’s marriage to Matilda had proved relatively unfruitful – she had only two children who survived to adulthood, a daughter (also named Matilda), and a son named William. William seems to have been a pleasant lad, though contemporary historian Henry of Huntingdon seems to have thought that his father shielded him too much from the harsh realities of court. However after he turned fifteen his father had him serve as regent for him in England when he was away in Normandy, perhaps a sign that he was attempting to groom the young man for rule. If so, it was a wasted effort. In 1120 the seventeen year old William, along with several of his friends (among them his illegitimate half-brother and sister) boarded the oddly-named White Ship, to travel from Normandy back to England. The King had been invited to travel aboard as well, but had already arranged to travel on a different ship. It was fortunate for him that he had. The ship had barely left harbour when it struck a submerged rock and capsized, killing all but two of the passengers. The flower of English nobility was wiped out in a single night.

William’s death left Henry’s plans in disarry. His wife had died several years earlier, so he hastily remarried in the hope of siring a new heir. In the meantime, he wound up nearly going to war with William’s prospective father-in-law, the Count of Anjou, when he refused to return the dowry that had been given to him. The Count then married one of his other daughters to William Clito, the son of Robert Curthose who had fled into exile when his father had been defeated. However Henry had this marriage overturned on the basis that the two were too closely related. William Clito then got the support of the King of France and began conducting raids into Normandy, but a wound on one of these raids turned gangrenous and killed him. Henry must have been relieved – his new marriage had proved childless, and fast running out of options to secure his dynasty, he had turned to desperate measures.

With no wish to see any of his nephews succeed to the throne, he was given another option when his daughter Matilda’s husband, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, had died. With Matilda a widow at 23 (she had only been twelve years old when she was married), Henry saw this as a sign and summoned his daughter home. She was willing to come – although she had become a respected figure in the German court, her husband’s lack of an heir had seen the elector counts place a rival of hers upon the throne, so she had little political future there. She thus returned to Normandy, where her father had conceived what (for the time) was an outrageous plan.

Henry’s plan was simple – when he died, Matilda (who still retained the rank of Empress) would rule as his successor, with her heirs then inheriting the kingdom from her. The nobles were outraged – the notion of a female ruler was almost inconceivable to them. In addition, Matilda had spent nearly half her life in Germany and was now more German than Norman. Matilda, for her part, might have been on board with the scheme – except that in order to give her a powerbase Henry married her off to Geoffrey, the teenage heir to the County of Anjou. Matilda was not pleased to be married to a man ten years her junior, and “only a Count” – hardly fitting for one with the rank of Empress. Henry, however, was not to be budged.

This may have turned out to be a miscalculation. Not only were Anjou traditionally enemies of Normandy, but this left Matilda well away from the English power centres most of the time. Although he brought her over to England to have the nobles wear their allegiance, she was soon back off to Anjou – where she bore two children, both male, Henry and Geoffrey. The second nearly rendered the whole scheme moot by killing her in childbirth, but she recovered even as her funeral was being planned. Aware of their lack of support among the nobles, Geoffrey and Matilda tried to persuade Henry to give them Normandy before he died, but he refused to give up his control. Before they could press the argument, Henry died – of “a surfeit of lampreys”.

Their fears proved well-founded, as the Norman nobles immediately began to dispute the succession, while Matilda was embroiled in a rebellion in southern Normandy. Ironically she was supporting the rebels, while her strongest supporters for the throne were with the royal army, leaving them all isolated. While they tried to honour their oath to bury the King so that they could leave for England, and while the other nobles argued, Henry’s nephew Stephen (a grandson of William the Conqueror through his daughter Adela) took his uncle’s example to heart and quickly seized the throne. Stephen was one of the wealthiest men in England, and he quickly managed to stabilise the realm under his rule. Matilda, however, was not going to give up her claim lightly. The eighteen years of civil war known as the Anarchy were just about to begin.

Pingback: Today’s Scribbling – Prelude To Anarchy – Daily Scribbling