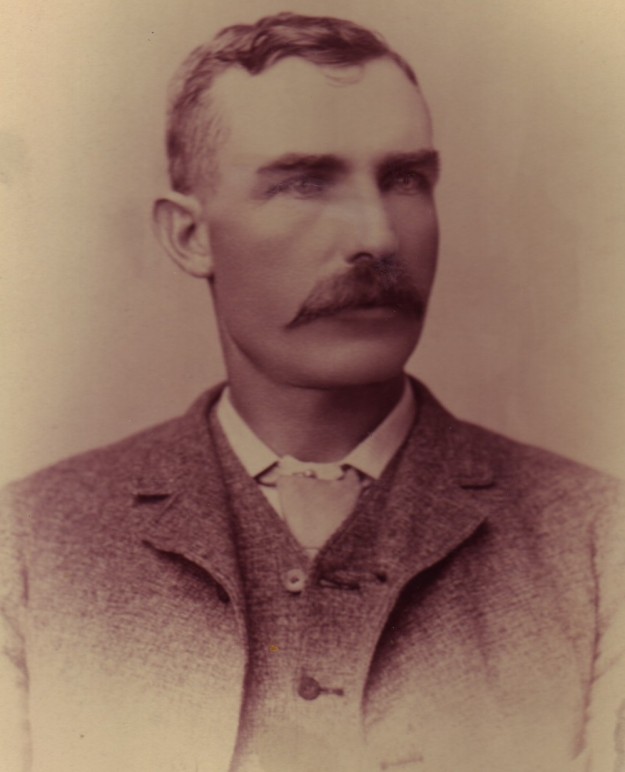

This is a true story, though it may sound like classic Western tale. I know it’s true, because it’s about my great grand-uncle, a man named John Doherty.

John Doherty was born in Donegal in 1851, but he and his brothers James and Joe headed across the Atlantic in the middle of the 19th century, to a town called Mora in what is now the state of New Mexico. They had a relative in the town named Thomas, who owned a large general store. The brothers were industrious workers, and found a good living for themselves out on the frontier – James being described as a “wealthy ranchero” in newspapers from the period.

John, in the meantime, became one of the most famous poker players in the West, and it is claimed that he carried around no less than $100,000 in gold (that’s just under $2.5 million in today’s money) to use as a bankroll for his poker games. He would only play No Limit poker, and would not play anyone who couldn’t match his stakes. Poker legends have it that he made the biggest raise in poker history, in a game against Texas cattle baron Ike Johnson in 1889 for the title of “Poker Champion of the West”. The bets on one hand began to rise, and both men were reaching the limits of their bankrolls, when Ike (determined not to be beaten) wrote out a deed for ranch and cattle, worth more than $100,000. John couldn’t match the raise, and knew that he would have to fold. Looking around, he noticed that the Governor of New Mexico was in the audience. Leaping up, he pointed a gun at the governor and said:

“Now, Governor, you sign this or I will kill you. I like you and would fight for you, but I love my reputation as a poker player better than I do you or any-thing else”

The governor hastily signed without bothering to read what he signing, and John threw it into the pot, declaring that he was raising “the Territory of New Mexico!” Ike folded, saying

“All right, you can take the pot. But it’s a damned good thing for you that the Governor of Texas isn’t here!”

It’s a good story, although it’s a bit unlikely for a couple of reasons. The first being that with his ranch and cattle on the line, I doubt Ike would have given in so easily, and the second being that John was, at the time, actually the Sheriff of Mora County, which means that he was not only an officer of the law, but a politician as well. Neither of those which would have made him want to draw a gun on the governor, although it could have explained his difficulties with his re-election the following year.

John’s association with the law in Mora county predates his election as Sheriff in 1886, as he is recorded as having been deputized by Sheriff AL Branch in 1880 to aid him in guiding a posse from Las Vegas (the New Mexican city of Las Vegas, not to be confused with the Nevadan Las Vegas) to a farmhouse where two fugitives who had killed the Marshall of Las Vegas were hiding out. The two men surrendered on the guarantee that they would be protected from mob violence – a promise that was not kept, as the two men (along with a third, who had been previously captured) were taken from the jail by about 100 locals and killed before they could stand trial.

The tradition of the head of a police department being publicly elected is an almost uniquely American tradition. It has the merits of making the police accountable to the public they serve, but the disadvantage of tying the police to the political landscape, and in forcing the heads of those departments to play politics in order to retain those positions. It was just such politics that John fell foul off in 1890.

John had been elected in 1886 on the Democratic ticket, but in 1890 he failed to secure their nomination to stand for re-election. Whether it was his reputation as a poker player interfering with his reputation as a sheriff, or internal party politics at work, we don’t know. Lending some credence to the notion of party politics being at work is the fact that John was not the only Democrat to lose out in the party’s primaries. So he and several of his fellow Democrats reached out to the New Mexico Republicans to establish a “People’s Party” ticket that they could seek election under, a tactic that earned him the nickname of “Judas Doherty” in the more fervently Democratic of the papers. Despite this tactic, he lost out at the ballot box to the man who had secured the Democratic nomination, one Agapito Abeytia Jr. Although he retained the title of “Sheriff” (as is traditional with elected posts in the US), John was Sheriff no more.

However he remained active in affairs in the state (or rather, territory, as New Mexico did not become a state until 1912), being one of the prominent citizens tapped to sit on the board that organised the Territorial Fair in (the New Mexican) Las Vegas. Whether he would have tried to reclaim the office of Sheriff again in 1894 we will never know, for the year before he could have stood he was murdered.

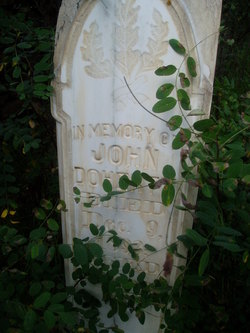

On the evening of the 9th of December, 1893, John Doherty collected his mail and took it into his office. There, he permitted two of his thirteen children (who ranged in age from a 17 year old daughter, down to a 1 year old son) to sit upon his knees while he read the paper. It was while he was engaged in this pursuit that his assassin struck. Perhaps there was some creak as the killer stepped up, as John is said to have commented on someone stepping onto the porch just before the fateful shot. Having rested the barrel of his gun on the sill of the glassless window that formed the top half of the office door (which, one can presume, opened out to the outside of the house), the killer fired a single bullet that went through John’s arm and into his chest. If his arm had not been in the way, the shot would have gone directly into his heart, killing him instantly. As it was, he lived long enough to tell his twelve year old son (who had immediately grabbed and cocked a pistol) not to shoot out into the darkness after the assassin – doubtless the lawman’s training at work, for such a shot would have been equally likely to strike a member of the household running to see what had happened. His last words, in response to those asking him what had happened, were reported as simply “Crime, crime! Let me die in peace.”

The assassination of such a prominent local figure, as one might imagine, sent the local people into a frenzy. His brother James immediately offered a reward of $2000 for any information on his brother’s killers, while the Governor offered a reward of $50, later raised to $500, for the capture of each and any of those involved.The sheriff, Mr Abeytia, who had been out of town at the time of the shooting, brought bloodhounds down to try to track the killers, but this tactic failed. Two goatskin masks were found discarded near the scene, alongside the tracks of two horse, leading people to presume that two men working together had done the deed. It was also discovered that the telephone lines out of Mora had been cut that night, presumably to hamper the organisation of pursuit.

The county jailer, a man named Juan Romero, was arrested in the immediate aftermath of the killing, although we don’t know on what grounds. He was soon released, however, and for several months the matter remained unsolved. However, in February of 1894, there was a breakthrough in the case. A man named Estanislado Sandoval, perhaps enticed by the reward money, swore under oath that one Juan Antonio Rael (a known “bad man”, who was said to have killed four men) had tried to recruit him to assist in the murder. Based on this testimony, a warrant was issued for Rael’s arrest. Sheriff Abeytia went out to Rael’s house in Coyote, New Mexico, but he wasn’t there. It was the jailer Juan Romero and another of Abeytia’s men, a man named Sostenes Lucero, who found him in a woman’s house in the town of La Cueva. Rael was not taken alive.

According to the deputies, Rael at first went willingly, but then tried to escape, somehow getting a gun and opening fire on them, so they had no choice but to gun him down. This was decried by local commentators, as it was clear that Rael, if guilty, was no more than a hired hand and his death left his employer off the hook. It was flat out contradicted by the woman in whose house he had been, who claimed that he had been shot while lying in bed, with no attempt made to bring him in alive. The death of Rael, in short, stunk. Stunk enough to draw the personal attention of the governor of New Mexico , one William Taylor Thornton.

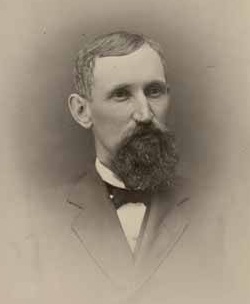

William Taylor Thornton was no stranger to violent death – he had fought for the Confederates in the US Civil War, in Missouri, before moving to New Mexico in 1877, hoping (like many at the time) that the drier climate would prove healthier to him. (As he survived to the age of 73, he may have been right.) He had been appointed as Governor of New Mexico by President Grover Cleveland the year before (with New Mexico being a territory rather than a state at this point, its governors were not elected), and had been charged with bringing an end to secret societies like the White Caps. He also made it his personal mission to stamp out politically-motivated assassinations. Not counting that of John Doherty, the previous ten years had seen eight politically motivated murders in New Mexico, three in 1892 alone. Taylor had previously personally involved himself on one such investigation the previous year, the murder of the police chief of Santa Fe, Sylvestre Gallegos, in a feud that took the life of at least one other man. That had been a much more straight-forward affair, though. Gallegos had been shot down in the street, in a duel of the type so common in Western films but so rare in real life, and his killers were well known. The deaths of Doherty and now Rael were far more obscured.

Questioning of the locals soon led Thornton to discover that Rael had spoken before his death of turning state’s evidence, having read of the reward being offered for information on the murder of Doherty. Thornton then had Rael’s body exhumed, and learned that, contrary to the story of the deputies, Rael had been shot six times rather than four, with the angle indicating that the shots had been fired parallel to Rael’s body, indicating that he had been lying down or in some similar position when he had been shot. Meanwhile, an examination of the jailer Romero’s coat showed that the bullet hole he claimed to have been made by Rael firing upon the deputies had actually been made by a gun held against the garment. Given the implications of the deputies having killed Rael to stop him from talking, Governor Thornton decided to take Sheriff Abeytia out of the loop, and enlisted Sheriff Cunningham of Santa Fe (where he had been mayor) to arrest Sandoval (who had made the accusation against Rael, and who had been held in jail as a witness since that time), and Bartolome Cordova (an associate of Rael who had let the deputies know where he was staying). He also had Sostenes Lucero, the man who had shot Rael, arrested. Cordova and Sandoval soon broke down and confessed to their involvement in the murders.

The two men admitted to having been part of the local chapter of the infamous Vicente Silva‘s Society of Bandits (also known as the White Caps), along with the late Rael, the jailer Romero, Sostenes Lucero and his two brothers Juan and Tomas, and several other men. The editor of the local newspaper (one EW Pierce, who was involved with the local political scene) had also been induced to aid them in their crimes.The head of local chapter, they claimed, was none other than the current Sheriff of Mora County, Agapito Abeytia Jr himself. While Vicente Silva himself had been killed earlier in the year, it appears that this local chapter had kept together, and were engaged in robbery, extortion and the occasional murder. The men feared that John Doherty had been engaged in gathering evidence against them, and could have gathered enough to implicate them not only in a series of thefts but also in the murder of a man named Jones in Colfax county. They had thus determined to kill him, with Abeytia conveniently out of town but returning to misdirect any investigation (as he did by securing the exoneration of the jailer Romero). It had actually been the twins Juan and Tomas Lucero who carried out the deed (possibly with the aid of a disgrunteld former employee of John’s named Chavez), with Abeytia deliberately delaying the use of bloodhounds until a rain had erased their scent. Following that, on the 17th of February Sheriff Abeytia had called a meeting of the band at the local jail, where he let them know that he had heard that Rael had been seen visiting the house of Joseph Doherty, and he believed he was planning to betray them. It was thus agreed that Cordova would determine where Rael would be that night, Sandoval would swear an affidavit that he had confessed to the murder of Doherty, and Romero and Sostenes would ensure that he was not arrested alive.

Sheriff Cunningham was thorough, and almost the entire band were soon arrested to stand trial for the murders they had committed. Among other things, it was discovered that Abeytia had embezzled over $13,000 from the county accounts since he had become sheriff. The sole escapee, Tomas Lucero (one of the twins who had actually performed the murder of John Doherty) was arrested that October by Sheriff Cunningham, who had been quietly tracking him down over the intervening months. Assisting him in the capture was Joe Doherty, bringing to justice the men that had killed his brother. Joe was himself elected Sheriff the following year. He would not stay in Mora long though, and would soon set off on a course that saw him rise from living in the backroom of a small shop to becoming one of the wealthiest men in New Mexico – but that’s another story.

The descendants of John Doherty and his brothers still live in state of New Mexico where he was laid to rest, so far from the hills of Donegal where he had spent his boyhood. Though his quest to bring the murderous gang to justice led to his death, it was his death that spelled their doom in the end.

Pingback: Today’s Scribbling: Death of a Sheriff – Murder and Conspiracy in the Old West – Daily Scribbling

Pingback: Today’s Scribbling: Death of a Sheriff, Revised and Expanded – Daily Scribbling

Pingback: American Policemen And Their Moustaches - HeadStuff

They Made a typo the name was A.L Branch. My great great grandfather he was sheriff in Mora in 1880

Thanks Max – updated!

I was wondering if the last name was really Blanchard . And, maybe shortened. My great grandmothers maiden last name was Lefebre. Born in Mora .I beleive her parents had the last name Blanchard who lived in Mora . My grandmothers sisters last name was Alarid. The Blanchars came from Missouri & canada

Hello I’m related to the Blanchard of the lefebres as well . I’m not sure where they were from the Blanchard was spelled branch and branchal so. I guess spelling wasn’t important . Interesting article. Thank u for sharing

John Doherty was my great grandfather. I’d like to ask you some questions about this story. It is far more detailed than any other versions I have heard. Thank you for writing it

No problem – just reply with your email address and I’ll drop you a line. (And don’t worry – if I don’t approve the comment, nobody else will see it.)

Time got away from me. Email is chanjamf at hotmail.com

Hello. Can you tell me the name of Mrs Doherty?

My great grandfather and his brother Cornelius also came from Donegal and were merchants along the Sante Fe trail to Mora NM around 1865.

In the 1920 San Jose CA census 19 year old Helen Dougherty and my Great Aunt Margaret Gildea age 50 (both teachers) lived in the same boarding house.So I’m wondering how or if they are related. If you can shed some light on a few missing details, my siblings, cousins and I would be thrilled to death.

Thanks

Eileen

Hi Eileen,

Sadly it’s been several years since I wrote this, and I don’t have my notes handy so I can’t tell you what John’s wife and children were called. I can tell you that there were quite a few Donegal Doherty emigrants (who used the Doherty and Dougherty spellings pretty interchangeably) going all the way back to the 1770s and probably earlier. So it could have been a relative, but it could easily not have been as well.

Eileen – I have a lot of information on the Gilday and Doherty line. I also have contacts with other descendants. feel free to email me.

Hi this is your cousin from New Mexico I am running the Folsom Museum which was Joe Doherty‘s mercantile store who is my great great grandfather. I ran the story on Facebook on our site. If you want me to take it down I will. I sent an email once before I’m not sure if you received it. My email address is . Look forward to talking with you

Matt Doherty

Hi New Mexico cousin. I don’t think I got your email but would be so grateful to get any information you have about the Gildays and Doherty’s. I have been trying to find any information about Great Aunt Bridget Gilday who married a Doherty. I checked the Folsom Museum FB page. What story are you referring to? Thanks. Eileen

Hi Eileen – this was a reply to a comment I made on the FB page because someone had copied this in here but not linked back to the original. (I snipped Matt’s email out before I published the comment so as not to get him exposed to spambots.) He runs that page so if you leave a comment there he will see it. All my info about the American Dohertys is in this article.

Hi there. Based on oral family history from my grandmothr, a Doherty had a son (not sure which one) who fathered a daughter (Eufelia Estella “Stella”) with Ines Pacheco. However, the story was Stella was fathered by a judge’s son. Never heard about a sheriff’s son. To your knowledge, were either of the Doherty brothers a judge. Only census records I found were for James as sheriff.

Hi Michelle,

I didn’t hear anything about either of the brothers or their cousins serving as judges, but it’s not impossible. I’d suggest reaching out to the Folsom Museum on Facebook – they’ve got a lot more info around this than me.

My Grandfather George Doherty was the youngest and was sitting on his knee. George had the store in Hoehne, CO. Smart Irish guys and gals!