There’s a Donegal band with the improbable name of Goats Don’t Shave, and they have a song called Las Vegas in the Hills of Donegal. For many people it’s an unofficial anthem for the county, and the chorus goes:

“And if I could, I’d build a wall around old Donegal,

To keep them out, both North and South, by God I’d build it tall.”

Many sympathise with the sentiment – Donegal has a strong independent streak after all. Only one place in the county has ever actually tried to put it in practice, however, and that was over the one thing an Irishman values more than anything – whisky. This is the story of the short-lived independence of the Poitin Republic of Urris.

Poitin is, to put it simply, Irish moonshine. Ireland is the birthplace of whisky (the name coming from Uisce Beatha, the “water of life”), where it is claimed that monks returning from pilgramages to the Mediterranean brought back distillation techniques that were then applied to the local grains. Whisky distillation became a popular croft industry, though not all the small local producers could get hold of grains, so often potato peel was used instead. The spirits from either of these mixes became known as “poitin”, or “little pot”, after the small brass stills used to produce it (though nowadays the term is usually used for the potato version). Poitin became ridiculously popular both as a drink and often for use in medicines, at least partially because no cheaper alternative was available. The big increase in its appeal came in 1661, when an excise began to be levelled on whisky. Initially small, it grew over time, and dramatically increased from 1s a gallon to 6s a gallon between 1785 and 1815, in order to fund the war with Napoleon. Naturally, brewing locally with a tax of 0s a gallon became an attractive proposition.

It’s not that surprising that Inishowen became a centre of the illegal distillation industry. Remote and barren enough to allow the secret distillation to go on, but close enough to a major port city (Derry) to allow it a major market, Inishowen flourished. In fact, Major Bellingham Swann, the Inspector General of Excise and Licenses of Ireland, estimated that 43% of the private distillers of Ireland were based in Inishowen. The government were well aware of how much revenue was being lost to this illegal trade, and in 1785 they passed an Act making unlicensed private distillation illegal. Large distillers received licenses and were forced to pay the duty, cottage distillers began to be stamped on quite thoroughly.

The government initially went after the distillers themselves, but often found equipment abandoned or even gone by the time they got there. Watch systems developed during the period of the Penal Laws to protect those illegally attending Catholic Mass were resurrected to protect the distillers – lookouts on hilltops, and even a relay of burning torches to spread the word at night. One priest was prosecuted for ringing his church bells when the revenue men approached. Soldiers were attacked with stones, revenue officials were attacked, and one family suspected of being informers had their house burnt down. The hornets’ nest had clearly been kicked.

Thwarted in dispensing individual justice, the government decided that collective responsibility should be applied, and so the system of “township fines” came into effect. Any parish where a still was found was fined, and the fines increased with the number of stills found. The fines were very high – a townland that normally paid £250 annually in rent might find itself paying £300 or more in fines, often leaving the landlords out of pocket. The loss of income from the poitin export also hit the landlords’ pocket, as even without the fines tenants could not afford their previous rents. Left homeless by the fines, migration to Derry became common, and a large number of Catholics living in the Bogside can trace their ancestry back to refugees from the “Inishowen Whisky War”.

Of course, the fines were not always paid quietly. The Ribbonmen were a secret society of Catholic tenant farmers based in Donegal, Leinster and other parts of the northwest. They came into existence during this period and received a lot of members from those affected by the poitin crackdown. They became infamous for battles with the Orange Lodge, often with innocent bystanders caught in the crossfire. They also targeted anti-poitin crusaders such as the landlord Norton Butler, who was assassinated in 1815. However one townland, facing severe fines for poitin-making, came up with a more elegant solution. And thus was born the Urris Poitin Republic.

The geographical location of Urris was key to the success of their plan. A townland of gentle rolling hills on the western coast of the Inishowen peninsula, it enjoys a sheltered harbour on one side, while the other is dominated by the great mountains of Croagh Carragh, Mamore and Raghtin More, which between them almost seal the entire area off from the mainland. The only entry is through Mamore Gap, a narrow high pass between two almost sheer hills lined with loose boulders.

The centre of Mamore gap, looking down into Urris.

The shrine is part of a larger structure that marks the location of St Eigne’s Well, one of the famous Holy Wells of Ireland.

What the people of the townland did, then, was simply to collapse the pass. With it blocked, any attempt to disassemble the blockage could be discouraged with stones hurled from above. (Some stories even have them arming themselves with cannon taken from a wrecked British frigate and using those to defend the pass.) So for three years the people ruled themselves. They had their fishing boats, and their farmland, and they were basically self sufficient. Finally in 1815 the British attacked in force, and overwhelmed the crude defences with “over a hundred shots fired”.

Thus the independence of the Poitin Republic came to an end. In truth, the end of widespread illegal distillation was soon to follow. Firstly the end of the wartime excise duty made legal spirits more affordable, and thus made the risks of poitin-making less worthwhile. Secondly, the spiritual dangers of poitin-making became a factor, as the local Catholic bishops of Raphoe and Derry (both Temperance supporters) declared the brewing of poitin a sin, and not just any sin but a reserved sin that could only be forgiven by the bishop himself. With both skins and souls at risk, and with the rewards much less significant, poitin making became far less attractive.

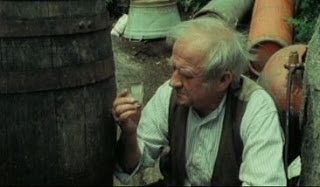

Cyril Cusack as an illegal distiller in the 1977 film Poitin.

The first theatrical film entirely in Irish, it pulled no punches in showing the downsides of the illegal trade.

Of course, not all the poitin-makers gave up on their trade. In fact, even to this day it would be rare to find an Irishman who hasn’t tasted the illicit spirit. While the wholesale production ceased, the spirit of the Poitin Republic, and the right of a free man to brew his own whisky, lived on.

Pingback: Today’s Scribbling: The Poitin Republic of Urris | Daily Scribbling

excellent research and thanks for sharing. It still feels true to us as we come over the gap home from america each summer that we are entering the private kingdom of urriss where the days are beautiful and everybody is a cousin and friend. My kids write about it at at school this way.

Enjoyed reading this thank you

Pingback: Mulroy Bay, Irish Poitín, 47% | WestmeathWhiskeyWorld

great information and reference to poitin stories . Being a poitin maker myself it is quite accurate and the recipes are quite various . However; Inishowen , Dun nGal was one of the main bandit counties in Ireland ,before it went to the United States . many a poitin man went over during the U.S prohibition was given a lot of money by the Mob ( Al Capone ) to educate the men in working the stills . but it’s nice to see it still living , The Real Poitin . Go raibh mile maith agat agus go mbere muid beo ar’ an’ amseo aris 1 . Dia do beatha Dun naGal ta’ go halinn agus go hiontach !. 🙂

Haha, I never thought of that before but I love the idea of the poitin men going over to teach the moonshiners their trade. There’s a movie in that.

When I was a child in Carndonagh where I was born, I used to hear the story of how the Bishop excommunicated most of Glengad for brewing poteen. The story was, be it true or false, that they would rather give the children poteen than food and this led to terrible heartbreaking living conditions.. the Republic of Urris is a new one on me. The McConolouges and Dohertys might still create one.

Is that George Doherty who ran a pub with his wife in Carn?