Donegal, as with most parts of Ireland, appears to spawn poets naturally. There are famous names such as William Allingham whose poem The Faeries is frequently referenced in modern works. (It’s the one that begins: “Up the airy mountain, down the rushy glen, we dare not go a-hunting for fear of little men…”) There are modern Gaelic poets such as Cathal Ó Searcaigh, and historical Gaelic poets such as Niall MacGiolla Bhríde, who was famously defended by Patrick Pearse for the crime of displaying a sign written in Gaelic-style letters. But there are few who started so low, or flew so high, as Patrick MacGill, the Navvy Poet from Glenties town.

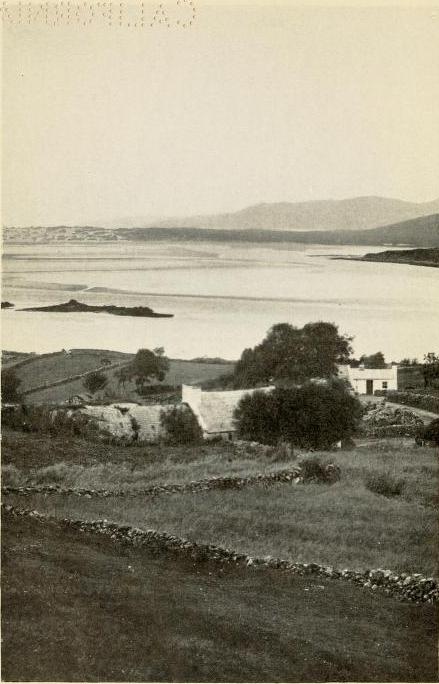

The house in Glenties where Patrick MacGill was born.

Image from the frontispiece of Songs of Donegal

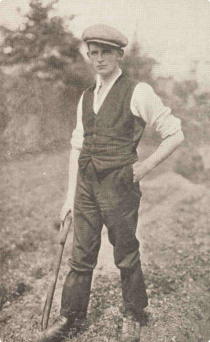

Patrick was born to a poor family living on the side of a mountain near Glenties in 1890. His childhood was generally unhappy, and his later semi-autobiographical work speaks of Irish life at the time as being held in debt slavery to the “gombeen man”, or local moneylender, while simultaneously being bullied from the pulpit by a local priest who ruled the town with a fist of steel. At the age of 14 he was sent to the hiring fair at Strabane, which he would later describe as “the slave market of Tyrone”. This was common at the time, as Irish families were generally too poor to support any extra mouths. He worked as a labourer on a variety of farms, eventually travelling over to Scotland to harvest potatoes in one of the groups that would go over for the harvest. Quite why he decided to stay in Scotland is unclear, but the protagonist of his novel Children of the Dead End made the same decision after he lost the money he had made “tattie-howking” in a gambling den, so it is possible that he had the same misfortune. (In fact, several of his later poems dwell on the evils of gambling.) If so, then in later life he might consider that gambling loss the most fortunate mistake he ever made. If he had returned to Ireland he might have disappeared into obscurity, but instead he moved into the profession that became associated with his name – that of Navvy.

Navvies were a breed apart. The name came from “navigational engineer”, and referred to their original role of working on creating the canals that connected English towns. Canals became railways, and by the time Patrick joined their ranks, railways had become roads, but the navvy remained constant. A tireless worker and a ferocious drinker, navvies were paid well by the standards of the time, but they earned in both sweat and blood. Safety standards at work were non-existent, and a navvy’s work often involved perilous situations (digging tunnels without supports, using explosives), but speed was paramount and lives were sacrificed to the improvement of infrastructure. Patrick, however, spent his money on books rather than booze, and taught himself to read French and German from dictionaries. For his own education he translated the works of Goethe and La Fontaine, and read Les Miserables in the original French. The literature of the oppressed woke something inside him, and his own novels would carry a similar social consciousness (as one of the few working-class writers of the time) that still evokes emotions today. In 1911 he had his own book of poems, entitled “Gleanings from a Navvy’s Scrapbook” printed. He went door to door selling it for sixpence during his spare time, and was lucky enough to sell a copy to Neil Munro, a writer and journalist who was on good terms with most of the prominent British novelists of the day. He had been partially responsible for bringing Rudyard Kipling and Joseph Conrad to public attention, so perhaps there was some calculation in Patrick selling him a copy of his book. Regardless, Munro was captivated both by the poems and by the evocative introduction in which he described writing his verses in a navvy’s hut with three men arguing about a boxing fight on one side, and four men arguing over a card game on the other. Munro wrote a column for the Glasgow News about MacGill and included his favourite poem from the book. The column wound up being picked up and syndicated as far away as New Zealand, and just like that, Patrick MacGill was famous.

The book immediately sold around seven thousand copies, and Patrick received several offers of work. Initially he went to Fleet Street to work for the Daily Express, which must have been quite a change for him. However he soon left when he was offered an even more prestigious post. Canon John Neale Dalton had been the personal tutor to the sons of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert (who died in an influenza epidemic), and Prince George, later King George V. Dalton was a famous scholar, and sought an assistant to aid him in translating ancient manuscripts. It may be that it was Patrick’s personal translation of German and French works that gained him the post, but it was a dream job for the man who had once described a bookshelf as a magical construct, allowing him to commune with the dead.

“My Book-case, and a Kingdom’s mine,

When falls the night across the earth,

And burns the fire upon the hearth,

When tools lie idle by the line.”

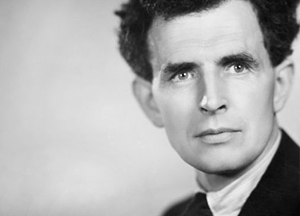

It was during this time while he was working for Canon Dalton that MacGill wrote the two novels that would establish him as a serious writer, as well as a poet. The first, Children of the Dead End, is a thinly-veiled piece of autobiography, and it is from this that we can get many details of MacGill’s early life. His protagonist, Dermod Flynn, grows up in Glenties, travels to Scotland as an itinerant farm worker and stays as a navvy. His mixture of lyrical Irish-style prose and unflinching social realism was a hit, and the book sold ten thousand copies in a fortnight – a huge success for the time. The book was not popular in Ireland however, due at least in part to his portrayal of the Catholic clergy as being just as oppressive as the landlords, moneylenders and police. His second novel, The Rat-Pit, was not destined to win them over. A companion novel to Children of the Dead End, it tells the fate of Dermod’s childhood sweetheart Norah Ryan, who bears a child out of wedlock and is ostracised from society, eventually descending into prostitution and death. The treatment of such women would be a hot button issue in Ireland fifty years (and even a hundred years) later. At the time,it was explosive. Quite where MacGill’s radical views would have led him to next is hard to say, because the following years was 1914, and, as with so many young men in their twenties at the time, Patrick MacGill’s life was about to be forever altered by the collapse of European politics that led to the outbreak of the First World War.

Patrick signed up in the 2nd London Irish Battalion as a rifleman, though he would later observe that he and the Colonel of the regiment were the only Irishmen in it. He would go on to write several books about his time in the regiment, but by the Battle of Loos in 1915 he was a stretcher-bearer – one of those fearless souls whose job it was to go out under enemy fire and drag the wounded back for treatment. This was no gentlemanly war, and those who took this duty often wound up as casualties themselves. Patrick, however, did not fall to the enemy weapons but rather to those of his own side. The Germans had been using poison gas shells for several months, and the British had decided to do the same, but a calamitous change in weather led to their own men being gassed, Patrick among them. He survived, but was invalided home, no longer fit to fight on the front. Instead, he was about to fight a different kind of war.

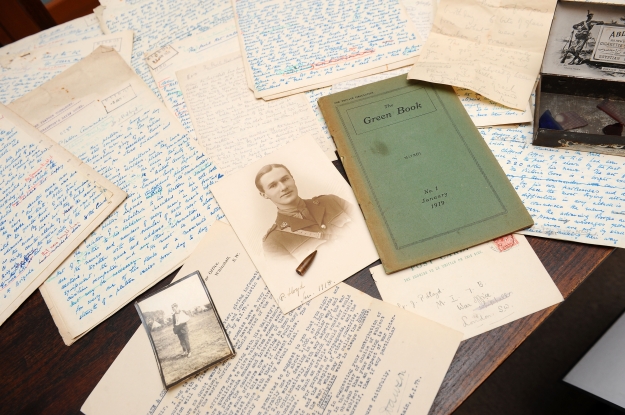

The MI7b papers found by Captain Lloyd’s nephew, Jeremy Arter.

Image via Will Humphries’ excellent detailed article on the story

In the early days of the 20th century, mass media had become a fact of life. Newspaper reports of the Crimean War sixty years before had often wound up forcing government policy, and so by this point the importance of newspaper coverage was well established. The modern perception of World War I is so coloured by our knowledge of the reality of the war, and the works of poets such as Frost and Sassoon, that it is often forgotten that at the time the public supported the war. This was down, to a large extent, to the efforts of an obscure government department known as MI7b. MI7 was the Military Intelligence department in charge of censorship (department MI7a) and propaganda (MI7b). It was to MI7b that MacGill was assigned, along with other writers such as AA Milne (creator of Winnie the Pooh) and Lord Dunsany (a writer in the Lovecraft mythos). The department wrote around 7,500 articles between 1916 and 1918, but after the war most records of their work was destroyed. Today our knowledge of them comes from a large number of their records which were rediscovered in April 2013 by Jeremy Arter, the great-nephew of a captain from the unit, who found them when clearing an elderly relatives house. Captain Lloyd, who like MacGill was a war invalid, saved about 150 unpublished articles when he left the unit. He may have thought of writing a book about it, but never did. Among the articles he saved was a copy of The Green Book, a pamphlet compiled by MacGill and Dunsany as a private memento for the members of the unit in January 1919 and stamped by the Government “for private circulation”.

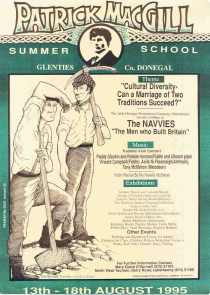

Following the War, MacGill returned to writing about Irish themes, writing a book of poetry entitled Songs of Donegal, and writing novels such as Moleskin Joe, about another character originally introduced in Children of the Dead End. He also wrote a play, Suspense, about a group of men in the trenches who realise that German sappers are tunnelling beneath them to plant a bomb. It was made into a film, and this may have prompted him to emigrate to the US in 1930. He made a cameo in a Noel Coward film called Cavalcade, and he had a play produced on Broadway, but in his forties he stopped writing, perhaps feeling that he had said all that he had to say. He died in Florida in 1963, aged 73, survived by three daughter and was buried in Fall River in southern Massachussetts, thousands of miles away from his homeland of Donegal. He is still remembered there, however, and the Patrick MacGill Summer School, held in his birth town of Glenties, is an annual venue for political discussion, debate and lectures, usually opened by the Taoiseach of the country. This year, on the fiftieth anniversary of his death, they debated, among other topics, the protection of the weak and vulnerable in society – a topic that the Navvy Poet, the voice of the working men, no doubt would have been up there debating with them.

Pingback: Today’s Scribbling: The Navvy Poet And The War Of Words | Daily Scribbling

I have accidentally found the “mine ” of Patrick McGill I am the son of a Donegal Man and this new treasure mine will offer more than gold.

Thanks, Michael – glad you like it! If you want to read the story of another man from Donegal named Doherty, my great grand-uncle John, you should read this page.

I am currently reading his three books on his experiences in the Great War, having a general interest in the same. They are utterly superb and a must for ANYONE with an interest in World War One.

I am a big fan of Patick MacGill and his writing. I had the honour of reading one of his poems on the RTE Radio Poetry Programme recorded at The Irish Literary Society in London a few years ago. I have most of his books including an original copy of “Gleanings from a Navvy’s Scrapbook”

Patrick MacGill was my mother’s cousin, so I thoroughly enjoy reading and collecting his work!

Thank you!

Hey! We’re related! Patrick MacGill was my mother’s father. Right now, I am going through all of my mother’s papers and what I am finding is fascinating. I am also a writer and I am working hard on a book about both of my grandparents and my mother and her sisters because they were all very interesting, totally brilliant human beings. My grandmother was a real character.

I HAD a ticket to London booked when the World stopped moving. I am doing a lot research still. Have you ever gone to the festival in Glenties? Do you live in Ireland? If Trump wins re-election I am seriously considering moving over there. My mother was born in London, I am allowed. Hopefully, still!

I have been to Glenties, as I have a friend from there (and I went to her wedding there a few years ago). I’ve never been to the Harvest Fair Festival though – maybe when the world gets a bit more normal! Good luck with your book.

Hi Lucy. I just found out that Patrick macgill was my granuncle. We must be related also 😊

Hello there,

I am currently research Patrick MacGill and Mrs Patrick MacGill….I am a native of Kinlochleven…my grandfather would have been working there at the same time as your grandfather…[I have recently completed an MA…where the subject of my dissertation was ‘Patrick MacGill: Irish Novelist – Framing the writer’…I would be interested to make contact..

M.logue@edu.salford.ac.uk – university address

mike.logue@btinternet.com – home address

regards Mike

He was my grandfathers older cousin as well.

Hi Denise, My small offering in my brief RTE debut is still available on this link – Click on Listen https://www.rte.ie/radio1/the-poetry-programme/programmes/2016/1224/840183-the-poetry-programme-saturday-24-december-2016/ Roy Foster was not stricly correct in his comments about Patrick in this programme.

There is also a book by a Liverpool Uni Student who is also related to PatrickMacGill – “Memory, Narrative and the Great War: Rifleman Patrick MacGill and the Construction of Wartime Experience” by David Taylor (Author)

I also act (very part time) as assistant curator of The London Irish Rifles Museum. Beir bua peter@powerhynes.com

Congratulations for the blog! I wrote a doctoral thesis about Patrick Macgill in 2009 and a couple of weeks ago (and thanks to a friend of mine from Glenties), I had the opportunity of donating it to St Connell´s Museum in Glenties. I´m leaving the link here: is in Spanish but at the end, there are very interesting documents (letters, newspapers, pictures and my private mails with MacGill´s family). I hope it seems interesting to you.

https://eprints.ucm.es/9711/

Regards,

José Manuel

Just found Patrick Macgill’s The Brown Brethren an excellent book.

Published 1917 during his time in the army on the Western Front j

It´s great to check that there are a lot of people interested in MacGill. I´m a big MacGill fan to the extent that I´ve most of his books (even a first edition of Sid Puddiefoot signed by him, a documentary aboout MacGill, starred by Stephen Rea, press clippings, documents…)When I donated my thesis about MacGill to St. Connell´s Museum in Glenties, I had the opportunity of meeting MacGill´s niece, Mary Claire O´Donnell, a charming woman. If any of you here is interested in talking about MacGill, contact me and I´d be glad about exchanging info. My mai is: josepulidopalomo@gmail.com.

Patrick was my uncle.

Hi, Billy!I´ve been trying to contact you, but I couldn´t find a mail. I tried using Facebook, but I don´t know if you check your account very often. I´d be very glad if we could talk or exchange info about your uncle.

My friend Syd Fogarty, sadly now deceased attempted to have the Navvy poet recognised in the City of St. Alban back in the 1980’s and entered into correspondence with the Glenties Summer School to make some cultural connection with the Irish dysphora here . MacGill was billeted in the City prior to embarkation and after Loos recouperated from his wounds in a house in Jennings Road St Albans which is now no more, but a later building occupies the site. A nurse who worked on the Psychogeriatric Ward at Hill End Hospital St Albans told of an woman patient there who remembers Sergeant MacGill and how as a child he would catch her when she slid down the bannester rail. In 1915 the special correspondent on the Hertfordshire Advertiser records meeting Macgill as he walked up Holywell Hill, St Albans. he tells how the young poet has enlisted in the Irish Rifles and he and the Colonel are the only Irishmen in it. He also refers to the clerical antipathy to his writings at home. Sadly my old pal never lived to see the cultural link come to fruition, but now there has recently been established, a blue plaque committee to mark sites of historical significance where idividuals of merit have stayed.. They have accepted my request to have Patrick MacGill included on the list.

Thank you for the amazing stories, Frank! I’m glad to hear you’re getting him a blue plaque, he deserves it.

I was wondering if you could list your sources for the dates and ages.

It’s been nearly ten years since I wrote this so I don’t have those details to hand anymore. Sorry.

Just reading about Patrick Macgill. School srarts today. He sure had a mighty career for one who left school at 10. Could only have been a genius. My dad celebrated his 98th birthday lat week and is a proud Glenties man, born and raised ahout 3 miles from Patricks birthplace