There are many castles in Ireland, but there is little debate over which is the most famous. Only one castle has been the site of visits from people as diverse as Sir Winston Churchill to Mick Jagger, from Nellie Bly to Laurel and Hardy, from Sir Walter Scott to Bernice Pauahi Bishop, last of the Kamehameha dynasty of Hawaii. The name of the castle has become not only a word in the English language but, for many, a key part of the Irish identity. I speak, of course, of Blarney Castle in County Cork, home of the famous Blarney Stone. The legend of the stone is that any who kiss it receive the gift of fair speech and skillful flattery. To do so is not without risk – the stone is set into the battlements of the castle, and those kissing it must literally bend over backwards to do so – a 1946 episode of the Sherlock Holmes radio series starring Basil Rathbone even has a man murdered through sabotaging his kissing of the stone. As one might expect from a legend that ties into the telling of tall tales, there are many different accounts of how the stone came to have its powers. Read on, to find out the truth.

Nobody knows who built the first castle on Blarney. The name comes from Bhlarna, meaning “small field”, and it was said to have originally been the site of druidic rituals, with a nearby stone circle as the focus of these. A stone from this circle, used in building the castle, is the fabled Blarney Stone. The castle was built on the site of an earlier, destroyed castle by Cormac Laidir MacCarthy, lord of Muscry and part of the powerful MacCarthy clan. They had even sent troops to Bannockburn to support Edward the Bruce, under the leadership of an earlier Cormac who was over-king of Munster at the time. In gratitude for their support, the Bruce gave them half of the famous Stone of Scone to return to Ireland, as it had been brought to Scotland by Fergus Mor mac Eirc, first king of Scotland, a thousand years before. The stone was passed down through the MacCarthy family until Cormac Laidir incorporated it into the castle he built in 1446, where it became known, after the castle, as the Blarney Stone.

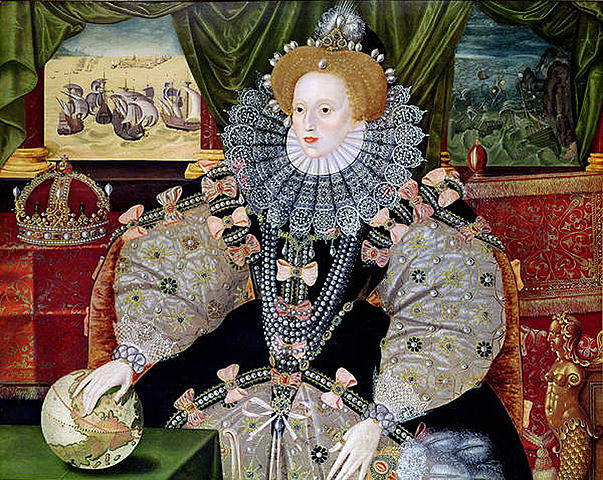

The goddess Cliodhna once loved a mortal man named Ciabhan and renounced her divinity to live with him. But while she slept,on the beach, her father Manannan Mac Lir sent a wave to carry her back home.

Picture is Prince Arthur and the Fairy Queen, by Johann Heinrich Füssli

Cormac Laidir MacCarthy was involved in a lawsuit, and prayed to the Celtic goddess Cliodhna for guidance (unusual for an Irishman in the 15th century to pray to a pagan goddess, but the old roots run deep). She told him in a dream to kiss the first stone he saw in the field on his way to the court, and he did, then argued his case with great eloquence and won it. He had the stone from the field incorporated into the wall of his castle – the famous Blarney stone. Cormac is also credited with saving the Blarney witch from drowning, after she had broken free from the Witch Stone on the estate where she had been imprisoned. In gratitude, she told him about the magical powers of a particular stone in his castle wall – the Blarney Stone.

The MacCarthys, as with all Irish clans of the time, faced pressure from the English. The Earl of Leicester was ordered by Queen Elizabeth to take possession of the castle from the MacCarthys, but the owner of the castle at the time, Cormac Ladhrach MacCarthy, put him off through letters filled with excuses and diversions. These were forwarded to Queen Elizabeth as “the Blarney letters”, and she took to calling any similar letters “nothing but Blarney”. The MacCarthys held onto the castle, until the Irish Confederate Wars of the 17th century – the Irish part of the War of the Three Kingdoms, the English part of which was known as the English Civil War. The MacCarthys supported the Catholic Confederates against the forces of Cromwell, and in 1646 Roger Boyle (better known as Lord Broghill), one of Cromwell’s generals, led an attack on the castle – motivated as much by the rumours of it holding the MacCarthy treasury as by the tactical importance of the castle. When his artillery broke through the walls, however, he found the castle deserted save for a few servants, who informed him that the inhabitants had escaped through tunnels connecting to the local cave system. As they fled, they are said to have thrown the treasure into the nearby lake, and several subsequent owners would try draining the lake to recover it, without success.

When the monarchy were restored to power in England, the castle was returned to Donough MacCarthy, who had gone from being a leader of the Confederates to a general in Charles II’s forces. He was also made Earl of Clancarty (an Anglicization of “Clan Carthy”). The family continued in service to the English military, with Donough’s eldest son Charles dying in the second Anglo-Dutch war. This would prove to be their downfall, however, as like many of the Irish nobility they chose to fight for James II in the Williamite wars. The 4th Earl, named like his father Donough MacCarthy, was actually given a Protestant education at Oxford at the insistence of his Protestant mother, however he was heavily influenced by his uncle Justin MacCarthy, who was a personal friend of the future James II. When he took part in the resistance of the Jacobites in England he was captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

He escaped in 1695, and joined James II’s court in St Germain, but two years later he sneaked back into England to try to retireve his wife Elizabeth, whose father, the Earl of Sunderland, hated him. They had been married as children in a political move by the king, their marriage never even consummated, and he had not seen her in years. She at first refused to see him, but he (having clearly kissed the stone) eventually persuaded her to let him in and they went to bed together in Norfolk House in London. One of the maids informed the Earl of Sunderland, however, and he had a group of soldiers drag Donough from his marital bed to Newgate Prison. Elizabeth campaigned fiercely for his release (he having clearly made quite an impression), and eventually King William III granted him a pardon on condition of exile, allegedly as much to be rid of her constant petitions as anything else. The pair moved to Hamburg, where they would have two children, a daughter and a son. The son would become Governor of Newfoundland, fight on the side of Charles Stuart, and be the last of the MacCarthy male line.

The grounds of Blarney Castle include a Poison Garden, wherein are grown all the traditional poisons – tobacco, wolfsbane and castor oil.

Photo by Richard Tulloch

The castle, in the meantime, became the property of the Hollow Sword Blade Company. This was an intriguing legal entity which had originally been founded by royal charter in 1691 to produce “hollow-ground” rapiers, that is to say swords with a concave shape to the blade. The corporation was granted the power to purchase land and issue stock, and after the sword-making business failed financially in 1702 this aspect of it became far more valuable to the financiers of London. They used it as a shell to purchase some of the estates forfeited by Irish lords who had supported James II, including those of the Earl Clancarty. It paid for this not with cash, but rather by agreeing to take on army debt from the war at a more favourable rate than could be obtained on the open market. The members of the Hollow Blade syndicate also used their insider knowledge of how this would cause the general trading price of the debt to rise in order to realise a large personal profit. Using the Irish land as security, the Hollow Blade company went on for several years acting as an informal alternative to the Bank of England (the only legal bank at the time), until a stricter enforcement of the law against unchartered banking, as well as disputes to title of the territory it held in Ireland, led to it being dissolved – though not before it was key in forming the South Sea Company, and thus in precipitating the first great English financial crisis, the South Sea Bubble.

The South Sea Bubble, by Edward Matthew Ward.

Possession of Blarney Castle certainly gave the Hollow Sword directors the gift of the gab, as they fleeced the City of London for millions.

One of the assets offloaded early by the Hollow Sword Blade company was Blarney, which was bought by Sir James St. John Jefferyes, the Governor of Cork City. He built a mansion attached to the old keep, but in 1820 this caught fire and burnt down, and was never rebuilt. The keep was abandoned, and remains so to this day. In 1846 Luisa Jane Jefferyes, heiress to the family, married Sir George Colthurst. He built her a new house in Blarney, at an elevated site near the castle, in an effort to console her after the death of her children. This house is still standing today, and it is in the gardens of this house that Blarney Castle now stands, attracting thousands of visitors annually.

Francis Grose, 18th century proto-troll and a man with literally nothing better to do than waste your time. Naturally, a personal hero of mine.

Quite when those visitors began arriving is a matter of some debate. The earliest verifiable reference is from 1785 in “A Classic Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue”, a fascinating book by Francis Grose. Grose was independently wealthy and passed his time travelling around the country documenting local folklore, along with recording the slang of the common folk – which is, of course, of singular interest to modern historians as a window into the lives of ordinary people of the time. He describes the Blarney stone as “on the very top of an ancient castle of that name…extremely difficult of access so that to have ascended to it was considered as a proof of perseverance, courage and agility…many are supposed to claim the honour who never achieved the adventure”. Here, to have “kissed the blarney stone” is used to mean one who tells a marvellous but false story – ironically different from its modern usage, as those with the gift of the gab are those who did not kiss the stone but who merely claimed to have. Still, the magical property of the stone soon became a fixture in the public imagination, and when Irish humorist added some verses to the popular song The Groves of Blarney describing the magical stone, the legend went, to use the modern terminology, “viral”. Who it was that first made the pilgrimage to the ruined castle is unknown, but by the end of the 19th century it had become the essence of an Irish adventure. The myths rose up, with each local eager to explain the magic behind the stone, and each traveller eager to believe. In the end, then, there is nothing to be found but pure, unadulterated Blarney.

Pingback: Today’s Scribbling: Blarney Castle – The Truth Behind The Myth | Daily Scribbling

Donough’s son was not the last of the McCarthy Clan. I am a direct descendant—the 18th great grandson of Cormac Laidir Oge McCarthy.